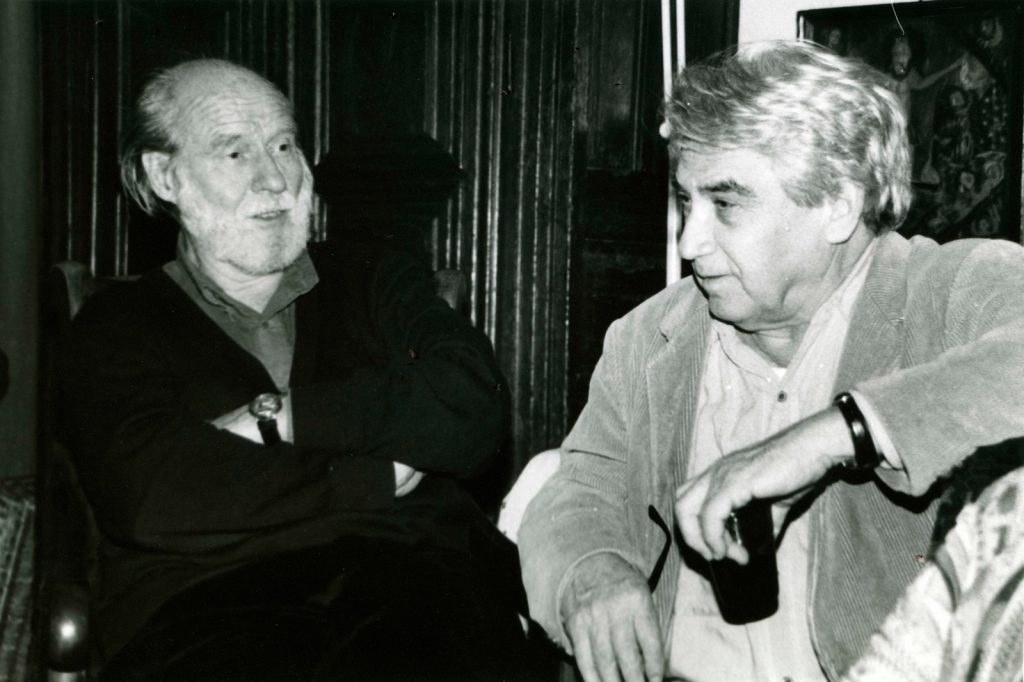

When one thinks about the work of Dutch artist Guillaume Corneille (1922-2010)– full of color, poetry, and inventive creatures and bestiaries– it is easy to imagine why he and Oswaldo Vigas became friends in Paris. Their interest in each other was also due to an empathy toward free expression, their passion for the so-called “primitive arts” (more precisely, for the arts of Africa, Oceania, and America). And, no doubt, a shared love of poetry.

Corneille never adjusted to the academic standards of art schools. Neither did Vigas. Before leaving Holland, Corneille had been attracted to the works of Matisse and Picasso, and to Surrealism. He especially liked Paul Klee and Joan Miró, and increasingly adhered to experimental forms, an interest he shared with another great Dutch artist, Karel Appel, whom Vigas also had the opportunity to meet. With Appel and the Dutch artist Constant, Corneille founded Reflex, or the Dutch Experimental Group, in 1948, which subsequently reconstituted itself as the international CoBrA group, with the participation of several other artists: the Dane Asger Jorn and the Belgians C. Dotremont, Pierre Alechinsky, and J. Noiret. The name “CoBrA” refers to the cities of Copenhagen, Brussels, and Amsterdam—the hometowns of its members. Theirs was an expressionist movement of international significance, closely linked to the Neo-Figurative trend that began to be in vogue in Europe and America.

CoBrA, which was active until 1951, distinguished itself by basing its creative processes on absolute spontaneity and freedom. The CoBrA movement was a way of opposing the constructivist trends by promoting an approach to painting that required vehemence and courage. The CoBrA artists were inspired by the folk art of their respective cultures, by children’s art, and by prehistoric art—all interests that were keenly shared by Vigas. Many years after this period in Vigas’s life, he spoke in an interview about archaic, prehistoric forms that were so important to his expressive and vital type of figuration: “The basis of art is in prehistory. It starts with humanity in caverns and caves. Modern art begins there.” He considered it essential to understand his work in connection with the past: “The most atavistic past, but the most remote.” This concept illustrates the relationship of CoBrA and Vigas’ art with Art Brut and children’s art: they all share a common point in the kind of immediacy of thought that the Surrealists promoted, without restriction or pre-determined reason. Also, they all especially appreciated the paintings by Jean Dubuffet and Willem de Kooning, artists who somehow opened up the pictorial guidelines of Neo-Figurativism, a movement that began to spread worldwide in the 1950s.

The idea of an unbridled art emerges in CoBrA declarations and other manifestations. In Vigas, this idea especially occurs in the paintings he made starting in the 1960s, after a brief but significant informal phase. In works like Huella Informe (1961), Cabeza Gestual (1962), Diablo (1962), and Géminis (1962) we see an orgy of gesture and color, in violent and spontaneous strokes. We see it in his Aparecientes series of that year, in his Cabezas and Formas espontáneas, and in the series made in the middle of that decade: his Personagrestes, Maria Lionzas, and Señoras series.

It is no coincidence that the French critic Jean Clarence Lambert called Vigas’ work “the Latin American CoBrA.” Lambert is one of the most diligent scholars of that group, and his comparison is not far-fetched, even if it is true that everyone in the group made their work at different times and in different circumstances. Vigas’ art belongs to Latin American Neo-Figurativism, a movement that was in turn originally related to CoBrA— though there is one aspect that in Vigas’ case takes on special importance: the certainty of, and security in, what he was doing. Vigas was not an artist of fashion. He always remained decidedly Vigas: an artist with clear objectives, open to change in his work, and always ready to socialize with those with whom, like Corneille, he was connected by spiritual or esthetic affinities.

Susana Benko

- Corneille with Oswaldo Vigas, 1993

- Corneille

Le hommedans la ville, 1952

- Oswaldo Vigas

Tabernáculo, 1954