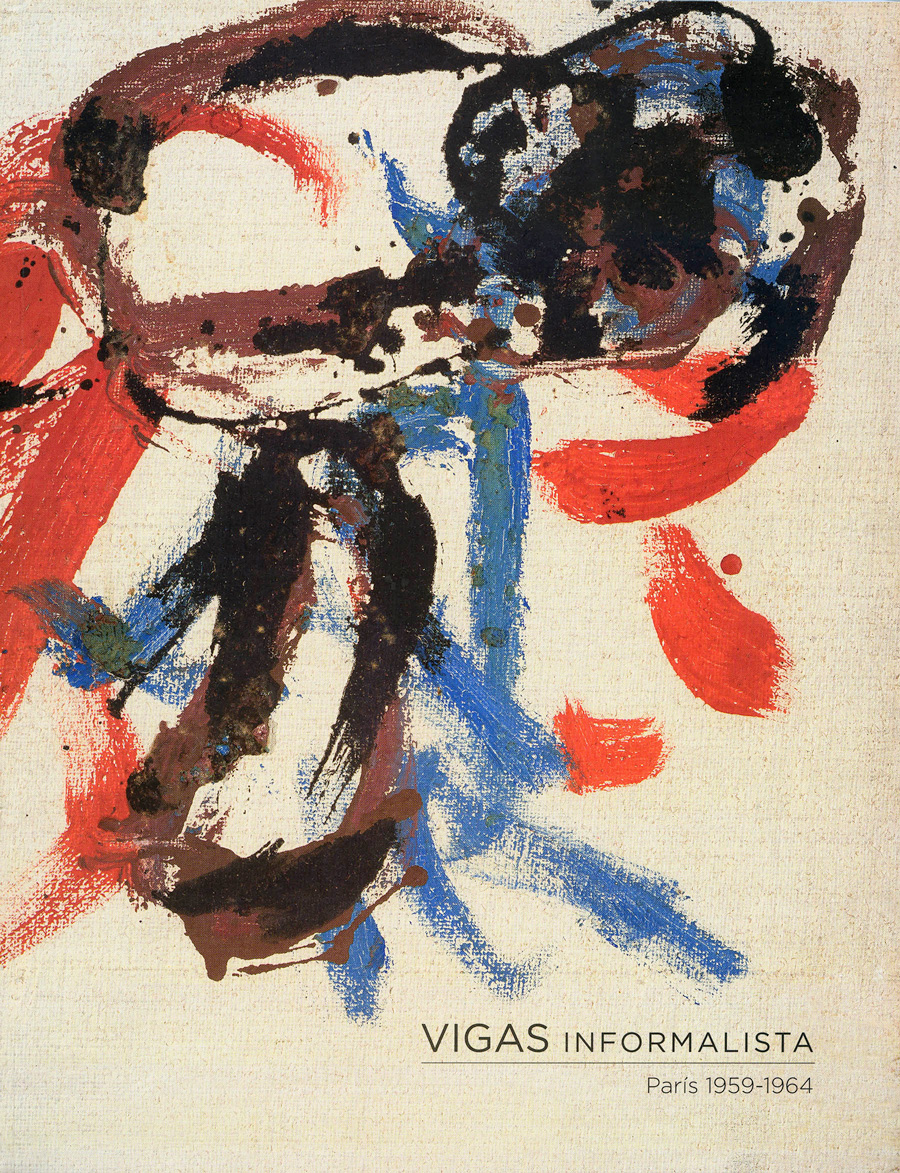

Vigas Informalista, Paris 1959-1964

Ascaso Gallery, Miami, U.S.

November 2014

Vigas Informalista, Paris 1959-1964

Marek Bartelik

In his house in Caracas, Oswaldo Vigas remained creative until his very last days.

This exhibition is his first individual show since he passed away, at the age of 90, on April 22, 2014. We may also call it his “first show”—not to suggest some kind of a causal break linked to this irreversible loss, but rather to stress his uninterrupted presence as a remarkable artist [1]. One might argue, in fact, that for an individual as deeply committed to his practice and process as Vigas was during his life, each of his consecutive shows will remain a first one, for each represents the essence of his existence, which for the artist is making art. His drive to make art recalled that of great painters, such as Henri Matisse, who at an old age, continued to work even when confined to his bed, insisting: “Space has the boundaries of my imagination [2].” And, like the French master, Vigas had an imagination that was unquestionably boundless.

This exhibition is the second show at the Ascaso Gallery has devoted to a specific and distinct moment in his artistic career, this time to the years between 1959 and 1964, a period during which Vigas’s work achieved a new level of expressiveness, abstraction, and heterogeneity [3]. Vigas’s paintings from that period reveal his interest in abstract expressionism and lyrical abstraction, while remaining distinct from the works he created before and after. The period under investigation was marked by two important trips, which were, in fact, two returns: in late 1958, the artist came back to Paris after a prolonged stay in Venezuela; in mid-1964, he traveled back to his native country, where he resided for the rest of his life. Between those two returns, there was the time for intense and prolific artistic activities, which resulted in a unique body of work, highly “Vigas,” as the artist would have said.

Vigas had lived in Paris since late-1952 and since 1956 had exhibited there regularly. In the first years of his sojourn in the French capital, he had studied art at the École des Beaux-Arts and later took philosophy classes at the Sorbonne. Recognised as an emerging talent associated with the post-war resurgence of figuration, he was later invited to participate in the bienials in Venice, Barcelona, and São Paulo. While asserting his presence as a painter, both internationally and locally [4], Vigas allied himself with a group of expatriate Latin American artists in Paris, a group that included Antonio Berni, Agustín Cárdenas, Jorge R. Camacho Lazo, Wifredo Lam, Roberto Matta, Alicia Penalba, Mercedes Pardo, and Fernando de Szyszlo. He also became involved with the review Signal, in which the writings of the critics Raoul-Jean Moulin, José-Augusto França, Jean-Clarence Lambert, and Karl-Kristian Ringström were published. All of these artists and critics advocated new approches to figuration with roots in both expressionistic tendencies in modern art and pre-Columbian art and cultures, the latter source treated as “prehistoric” and therefore universal. [5] In early discussions of Vigas’s works European critics stressed and praised his unique blend of Dionysian emotionalism, expressed in the very process of creating art, and employed as a form of direct communication with the viewer, which they frequently linked to his fiery, “Latin American” temperament. In 1957, Vigas described his style of that time in a more general and, one might say, more open manner as “[a] system of signs and symbols, a personal way of conceiving objects, figures, planes of color, lines, spaces [6],” pointing to the heterogeneity of his artistic language, which relied on a complex matrix of referents and modes of expressions.

During his stay in Venezuela in 1958, Vigas actively participated in artistic life there, as well as in the popular social movement that led to the overthrowing of General Marcos Pérez Jiménez, the dictator who had ruled Venezuela since 1952. In November, when Vigas returned to France, he found the country he resided in different than the one he had left. A few months later Charles de Gaulle would be sworn as the first president of the Fifth Republic, while civil war was raging in Algeria. There were significant cultural changes as well, particularly in the way the French redefined the meaning of their “high culture” and contemporary art [7]. That shift became clear when, in the following year, Pierre Restany published the “Constitutive Declaration of New Realism.” This manifesto equated New Realism with new ways of perceiving the real, “not through the prism of conceptual or imaginary transcription” but by dealing directly with reality—by which he meant the modern culture of consumption and mass media; it also declared easel painting a classical medium that “has had its day [8].” “Newness” was, in fact, a cri du jour: “New Realism” in art, the “New Wave” in cinema, the “Nouveau roman” in literature.

Upon Vigas’s return, his style started to change. In this period we encounter a new Vigas: constructivista turned into a rebellious informalista, as his approach to painting took a rather dramatic turn, this time toward a gestural style associated with abstract expressionism, the French equivalent of it called art informel [9], and what in Spanish became known as el informalismo [10]. That shift in Vigas’s art paralleled that of the artists often referred to as second-generation Abstract Expressionists [11], and in France the proponents of lyrical abstraction [12], who were dissatisfied with the growing presence of pop art and New Realism, as well as with a conceptual push toward neo-dada [13]. In France, the vitality of “heroic” figuration was reinforced by the presence of the “Old Masters” of modern art: Georges Braque, Fernand Léger, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso, as well as by the lasting appeal of existentialism with its emphasis on the human condition in which existence precedes essence. André Breton’s continuous advocacy of the importance of the surrealist spirit, with its affirmation of “convulsive beauty” and its interest in indigenous cultures also played an important role in keeping figuration alive, while critical thinking about the social and cultural significance of modern art was impacted by Claude Lévi-Strauss’s Tristes Tropiques, published in 1955, which popularized a structural model (rather than a psychological one) to evaluate social reality.

Despite the repeated calls for “The Fall of Paris” since the beginning of the Second World War, the French capital clearly remained a vital center from which new ideas about art radiated worldwide after the war [14]. However, those ideas were undergoing a rapid change on their own. As the art historian Catherine Dossin argues in her forthcoming book on the Parisian scene of that time, by the early 1960s ‘[n]ot only did Western Europeans rely heavily on the United States economically and politically, they were becoming dependent on its style, fashion and culture [15]. That “dependency” brought many more young European artists closer to pop art than to abstract expressionism, in part because at that time the latter was often perceived to be a derivative of European art, whereas the former was considered a genuine American expression.

Vigas never directly responded to the calls of American and British pop artists and French New Realists to bring art close to life by embracing the iconography of consumer culture. Neither did he fully subscribe to the prescriptions of Clement Greenberg, who advocated close attention to the surface of painting, and a confirmation of the flatness of the canvas, which influenced many artists in the United States and elsewhere. For the Venezuelan artist, such flatness derived not so much from the specificity of the medium of painting—a modern concept sui generis—as from the “primordial” aspects of art, which brought him closer to Jean Dubuffet and his treatment of materials for making art as “living substances” and to the CoBrA group [16]. Subsequently, the surface in Vigas’s paintings in the late 1950s and early 1960s remained highly visceral, oozing with thick paint while exposing a jarring self-awareness as part of the act of creation. Many of his paintings from that period emphasize the porous quality of the surface, as well as the brushwork; in these works, the paint often behaves as if it were volcanic lava, imposing its own gravity on the natural terrain of the canvas. But there is also something highly theatrical in his distortion of the figure, which reinforces its tragic qualities. Some of the protagonists in Vigas’s paintings might, in fact, appear to descend from Antonin Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty, the concept of which was influenced by Eastern forms of theater, but also by Artaud’s sojourn in Mexico [17].

In 1959-1960, Vigas painted a series of works with bold, rounded forms—abstract and figurative at the same time—which he tightly packed onto the flat pictorial space. Those works belong to the series “Piedras Fértiles (Paisajes y formas).” The expressions “fertile stones” and “landscapes and forms” suggest oppositions, but only if one treats them as abstract, logical constructs. Otherwise, they suggest a world of physical experience, in which past and present remain intertwined, benefiting from the tension and friction between them. Analyzing Vigas’s approach to space in painting, one might think about Hans Hofmann’s “push-pull” theory of movement, which relies on a combination of color, light and shape to animate the canvas, to make it “breathe,” as the artist discussed in his 1948 book The Search of the Real and Other Essays [18]. Hofmann wrote: “The artist’s technical problem is how to transform the material with which he works back into the sphere of the spirit [19]” Vigas would have agreed with Hofmann that the aim of the creative process is not to imitate nature, but to work parallel to it, to contribute to its growth.

Still, even if Vigas’s paintings from that series, such as Piedras fertiles II, 1959 and Paisaje mítico XII, 1960, might recall some of Hofmann’s works, they are much more visceral, verging on abject. Clearly, although both artists might think in a similar way about the formal requirements of modern art to assert its independence from Nature, each of them understands it in very different way. For the American painter Nature belongs predominantly to the realm of the beautiful, and ultimately the abstract, whereas for the Venezuelan artist Nature is quintessentially sublime, and therefore much more “unstable” in terms of being either abstract or figurative. Heavily on the side of the emotional, Vigas’s art is anti-classical—it belongs to the realm of passion and violence. It is in that dynamic realm that Vigas found a fertile ground to grow his forms in the late 1950s and early 1960s: he piles them on top of each other, layering them like geological cross-sections -Paisaje mítico IV, 1959-, or carves them out like crevices filled with organic deposits undergoing gradual decomposition -Piedras fértiles XV, 1960-. To convey a sense of the Sublime chromatically, the artist chose a Rembranesque palette, rich in blacks, browns, ochres, siennas, umbers, and vermilons, which is also reminiscent of Goya’s “Black paintings.”

While in Venezuela 1961 marked the beginning of a relative (and ultimately deceptive) political tranquility, France continued to be rocked by political and social unrest, culminating in mid-October with the attack by French police on a peaceful demonstration by the Algerians living in the country that left 40 people dead. It was also the year of a number of deaths among the prominent figures of French culture and the arts, among them Maurice Merleau-Ponty, George Bataille, Céline, and Yves Klein. Despite these disturbances, artistic life in the French capital remained vibrant, attracting new artists in search of fame, to the point that it was satirized in the 1961 British movie The Rebel (US title, Call Me Genius), in which the main protagonist, who moved from London to Paris to become a painter, splashes paint onto the canvas and rides a bike over it to achieve an effect similar to that of Pollock’s drip technique, as well as to Yves Klein’s “Anthropométries,” in which female models were used as “living brushes.”

In 1961, Vigas participated in the “XVIIe Salon de Mai” at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris—next to Jean Arp, Max Ernst, Gino Severini, Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, and Dorothea Tanning. Later that year he exhibited his newest canvases at the Galerie Neufville, with Ann Weber and Atilla (Biro). Hence, his works were presented on the one hand among those by leading European and American modernists, and on the other, in a context of the latest developments of international art, and in the company of many artists from the United States, whose work the Galerie Neufville vigorously promoted [20]. On the occasion of the show at the Galerie Neufville, the critic Michel Courtois noticed the change in Vigas’s work, calling the artist’s sensibility “more contemplative [21]”. French art critics continued, therefore, to emphasize the sensual and emotional aspects of Vigas’s art, but softer than before, and not necessarily “Latin American.” On his side, Vigas, like many of his colleagues from South and Central Americas, became preoccupied with the questions of how to understand his identity as a Latin American exile in Europe, but also how to distinguish himself from others in that same situation, and how to find the right relationship between difference and uniqueness. To answer such questions required him to look not just at unique aesthetics and creative temperaments, but also to address specific cultural and political concerns native to South and Central Americas, because for many the term “Latin American” often carried a connotation of activism [22]. Confronted with such a dilemma, Vigas found himself triangulating among French, American, and “Latin American” artistic traditions. At the same time, searching to protect his individuality, the artist remained responsive to broader human concerns.

In 1961, Vigas’s work underwent further transformation: he moved closer toward lyrical abstraction, which, as a “softer” offspring of abstract expressionism, opposed cubism, surrealism, and the pre-war École de Paris. Artists who worked in that style championed Claude Monet and Wassily Kandinsky, while paying close attention to the works of Bazaine, Nicolas de Staël, and Wols, as well as to the new “hot” artists, Georges Mathieu and Pierre Soulages in particular. Nacientes III, an oil on paper from 1961, shows, in fact, how Vigas experimented with a gestural style reminiscent of calligraphy; and his Concretizatión III, 1961 uses the technique of applying the paint directly from the tube onto the canvas, which by that time Mathieu had turned into a performance. But, here again, Vigas remains true to himself, probing the essence of his identity as an artist who looks back to prehistory and mythology for inspiration, open to the experience of others, but highly possessive of his desire to remain anchored in his native culture. Nowhere probably, is, this tendency as visible as in his large canvas Gran paisaje mítico, 1961. The landscape in it seems to be so “great” that the only way one can experience it is looking from high above. Seen through a sort of haze, it resembles an inchoate, cartographic mirage, its mythical dimension matching the description of a huge map Jorge Luis Borges described in an enigmatic, one-paragraph short story “On Exactitude in Science [23]”. In that text, Borges tells us that this “map-territory” has been deposited in an anonymous “desert of the West,” where it serves as an occasional shelter for beggars and beasts. Looking at Vigas’s painting, one might detect a similar search for “equilibrium” between art and life, in which decomposition and growth are part of the same process, where the West gradually decays, while the sun shines in the South.

In politics, 1962 was the year marked by the proclamation of independence in Algeria and the Cuban Missile Crisis, which put the world on the brink of nuclear war. In May the stock market crashed in New York, which had a dramatic impact on the art market, producing, as Dossin observes, waves of panic among art buyers, especially in Paris, from which emerged “a global cabal against abstract art [24]”. That year has been viewed as marking the emergence of pop art. For Vigas, 1962 belonged to another intense period in his own artistic life, during which he further engaged in probing the boundaries between figuration and abstraction on his own [25]. He exhibited in the Galerie Neufville, with Mariano Hernandez, Joan Mitchell, John von Wicht, and others, all of whom presented works painted in a gestural style and which would lead to his solo show at that gallery the following year. That show would confirm Vigas’s alliance with art that rejected “rationalist” tendencies, such as pop art and op-art, and embraced expressiveness as its main form of communication.

In 1962, Vigas’s search for blending figuration with abstraction achieved a new level of visceral sophistication in the series “Personagreste,” and the paintings with “cabeza” (head) in their title [26]. In those works the artist shifts attention from landscape toward the figure, which once again often appears as a mythological creature, its presence truly haunting. What distinguishes those figures from, for instance, his famous “Brujas” (“Witches”) [27], is that they are less totemic; also his new figures frequently appear in pairs[28]. Instead of a hypnotic and occasionally spine-chilling dance, as in “Brujas,” we watch couples in a passionate embrace, as in Personagreste IV, 1962. Insecto II, 1962 is one of the most intriguing images from this period. The oil on canvas depicts a creature with bulging eyes that recalls Vigas’s witches, but it is reduced to an anthropomorphized shape comprising just a few looping lines executed in bold strokes of red, blue and black. These brushstokes “carry” the emotional weight of the image, suggesting an intense discharge of creative (and possibly erotic) energy, while producing a highly painterly effect.

Again, critics were quick to notice the change. On the occasion of the exhibition “Martin Bradley, Byung, Vigas,” at the Galerie Librairie Anglaise in August 1963, Vigas’s paintings were praised again for being “gestural and strongly stormy [29]”. José-Augusto França called Vigas’s paintings: “An uplifting spectacle, maybe a little monstrous, of unforeseen dimensions: those black shapes, living snakes, menacing in oil compositions, are organized in his gouaches, joining the game of key gestures as a key to our reading, or as compasses marking the path [30]”. What all those critics stressed was a spectacular meshing of passion and lyricism, which, in fact, constitutes one of the main strengths of Vigas’s art, regardless of its stylistic particularities.

In 1964, the year of Vigas’s return to Venezuela, Georges Braque died, leaving Picasso as the last living pioneer of heroic modern figuration in France. It was the year when Robert Rauschenberg was awarded the Grand Prix at the Venice Biennial, which, for many, marked the real “Fall of Paris,” as the center of the art world moved to New York. In Europe, the influence of American culture both “high” and “low,” was on the rise. That phenomenon had already been brilliantly captured by Jean-Luc Godard’s debut masterpiece, “Breathless” (released in 1960), which depicts Paris as a mecca for adventurous young people, and where a French hoodlum (played by Jean-Paul Belmondo), modeling himself on the characters played by Humphrey Bogart, falls in love with an American exchange student (played by Jean Seberg), who likes William Faulkner, Mozart, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir [31]. But, in 1964 this was not exactly Vigas’s Paris, because, as Janine Castes explains: “Oswaldo didn’t feel “at home” in France any longer. Hence, at the age of thirty-eight, he chose to start a “new” chapter in his life by returning to his native country, where he became involved in making and promoting art with a new energy.

In 1964, Vigas’s individual show from the Galerie Neufville, which took place in the previous year, was enlarged when presented at the Fundación Eugenio Mendoza in Caracas. Among the works include in that exhibition were Naciente I, Gemini, both from 1962, and Vuelo ígneo, 1963. The two former works display once again a subtle interplay of figuration with abstraction, clearly Vigas’s signature style by then; the latter is a prime example of the gestural abstraction, closer to those of Cy Twombly than to Jackson Pollock’s, that characterizes Vigas’s works from 1963-64. While the linear forms “float” against the white and ochre background, they crisscross the surface, gently coiling, twisting, and turning, producing a modern figura serpentinata that sets the image into unending motion. Despite being a highly abstract image, one might detect in it the contours of two anthropomorphized, bird- and animal-like figures, one hovering over the other. Although the dynamics of that interaction is impossible to determine unequivocally (it could be a fight or an act of making love, or both), the image seems to be about the essence of human nature, where violence and love are often intertwined, and the expression of which gestural abstraction facilitates through the rhythmic action of the brush. One can also think about Vigas’s gestural style as a form of performative writing in the present tense: the movement of the artist’s hand becoming the agent of emotions, which he shares with the viewer. Consequently, what happens in Vigas’s painting happens in the present—physically, bodily, spatially—revealing itself splendidly right before our eyes.

Paradoxically, after his return to Venezuela Vigas ceased to be labeled as a Latin American artist, or at least, critics did not do so as frequently as before, and, when they did, that distinction became much more nuanced [32]. One might say that his homecoming allowed him to assert his position as a universal artist living in South America. That shift was already reflected in a text accompanying his first individual exhibition in Venezuela immediately after his return. Writing for his show at the Foundation Eugenio Mendoza, Raoul-Jean Moulin begins his introduction as follows: “When Vigas exhibits for the first time in Paris in 1956, his painting highlights the constraints of a trade: the seduction of applying paints, a discipline for static and definite forms. Closed on itself, it needed [his] response [33].” For the next years in Paris, Vigas took on a challenge to do just that, to “respond” with a spectacular result, which prompted Moulin to finish his text with this assessment of the exhibition: “We participate in a manifestation of a worldview related to the moral responsibility of action [34].” Those words happen to be prophetic: for Vigas that responsible worldview would remain a foundation for his art in the years to come.

Written by Dr. Marek Bartelik, current president of the International Association of Art Critics, on occasion of the exhibition "Vigas Informalista. Paris 1959-1964", presented in the Ascaso Gallery, Miami, from November 20, 2014 to March 30, 2015.

Endnotes: