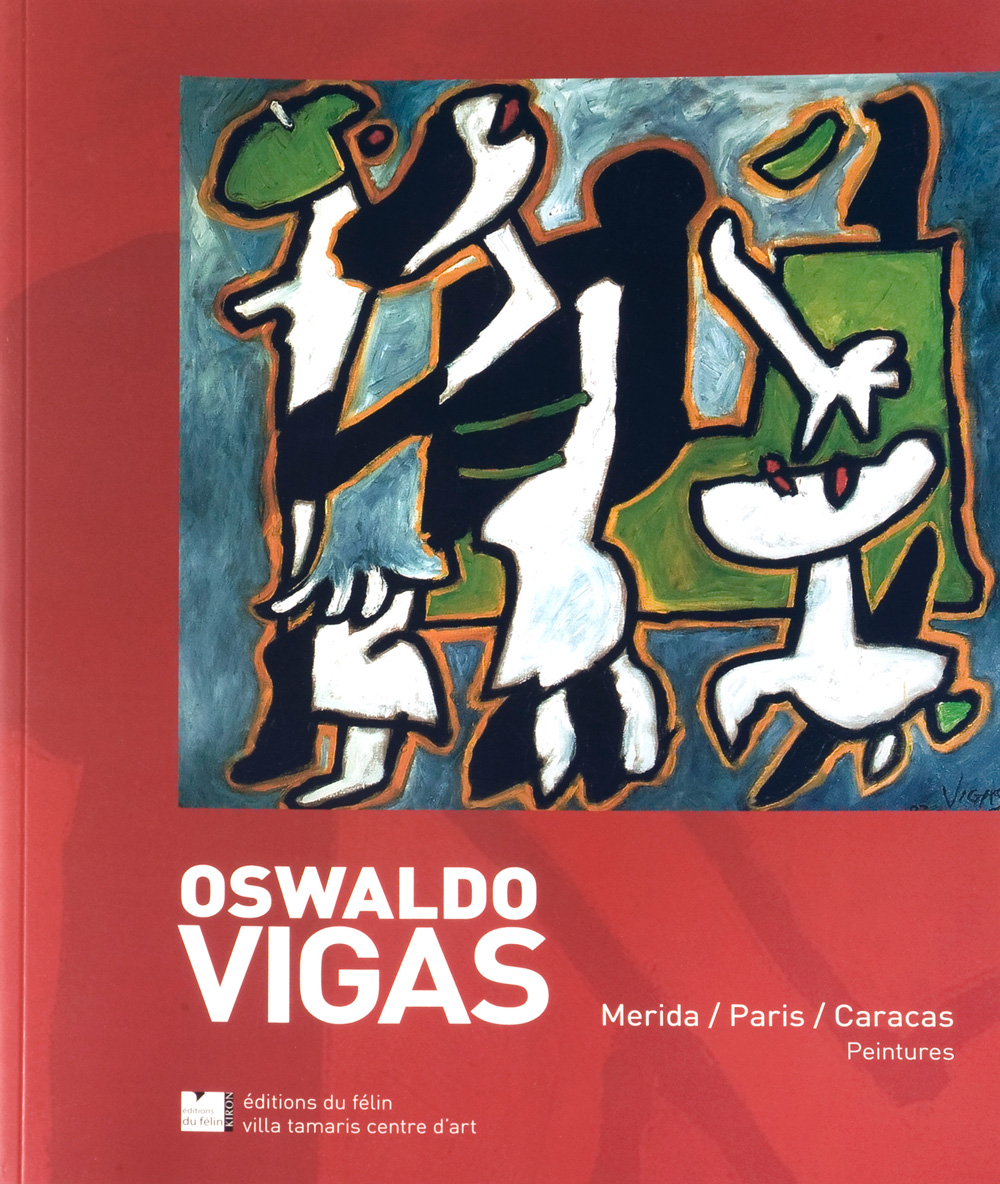

Oswaldo Vigas, Mérida / París / Caracas. Peintures

Villa Tamaris centre d´art, La Seyne - sur- Mer, Francia

2011

Oswaldo Vigas or the complexities of exile

Roberto Bonaccorsi

Mérida, Paris, Caracas... The title of Oswaldo Vigas’ exhibition at Villa Tamaris implies the idea, of course, of a tour, an itinerary. A journey, first, to the senses; a trip to a distant country with the implicit idea of pilgrimage. “He who paints, he who sculpts, in short, anyone who engages in art, has but one dream, aspires to a single goal: going to Paris. The big thing is there.” [1] An irresistible attraction to the capital of art [2] was developed from the late nineteenth century. Two big names of Venezuelan painting, Arturo Michelena and Tito Salas, frequented Jean-Paul Laurens' workshop. Arriving in Paris in November 1952, Oswaldo Vigas was not a beginner. At 26, he already had a medical degree, while he carried out an intense pictorial creation. Member of the Free Art Workshop in Caracas, in 1952 he won the National Visual Arts Award, the John Boulton and the Arturo Michelena awards. He took courses at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris (in Marcel Jaudon's lithography workshops), and confronted his peers in a relationship without reverence. He was immersed in the Second School of Paris (1945-1965), which was characterized by its diversity and even by its eclecticism, but Lydia Harambourg did not include him in her dictionary of artists. Was it an oversight? Rather, it was an indication of a gap in the original place Oswaldo Vigas occupies in this creative, complex, and contradictory explosion that characterized the post-war. This determined his artistic effervescence. The fact of not being tied to such an ecumenical school manifested in the young painter this freedom of aesthetic he will never let go. “From 1950, the road opens freely outwards and rejects the past. Under the impetus of Tapie, Estienne, Ragon and Restany, the new trials or currents debate, rival, wither or strengthen, expecting others to replace them. In times of the pressure of novelty and under the American influence, the pace of change accelerated, clearing up past experiences. Many new ties were woven over the years with the leaders of the movements that occurred abroad or in France: from Vigas, Lam or Guayasamín, from Léger to Masson, from Hartung or Schneider to Zao Wou-K, from Vasarely to Soto, from Cruz-Diez to Calder, from Corneille to Alechinsky, from Debré to Messagier or César” [3]. A fruitful time of debates, confrontations, of equally ferocious antagonisms that Gaston Diehl thinks retrospectively as a rebirth. Vigas' workshop on Dauphine Street quickly became a place of exchange that allowed him to rub shoulders with Manessier, Lam, Matta, Herbin, Dewasne, Doucet, Léger, Corneille, Max Ernst... and Picasso, of course, with whom he established a strong and intense relationship in 1954, from creator to creator. He visits him in Cannes (La Californie), keeping his distance: “I was always a little afraid of him devouring me” [4]. At the same time, he exhibited in several galleries (Neufville, La Roue) and in the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles, at the Museum of Modern Art in Spain, and in the United States (at the Pittsburgh International Exhibition of Contemporary Painting, 1955 - Museum of Fine Arts, Houston). Gaston Diehl's faithful friendship opened the doors of the Salon de Mai for him in 1953, and Vigas occasionally exhibited in his native Venezuela. Paris -open city, opening city- established itself as a center that allowed him to expand himself, to build bridges, to multiply contacts and the centers of interest. In 1959 he accepted the position of cultural attaché of the Embassy of Venezuela.

An exceptional vitality, a bustling activity that we can evoke in broad strokes. In Paris, Oswaldo Vigas combines the solitude of the creator with a strong sense of the collective. He rejects marginality in benefit of singularity. The existing influences (the beginnings of Surrealism, for example) and the interest in some schools (such as CoBrA) are revealed without voiding the originality of an intense focus on constant evolution with a profound social and aesthetic coherence that develops in the multiplicity of formal approaches. “Oswaldo Vigas is one of the true authors of Latin American art. Author, here, has a rather polemical sense in these times generally addicted to loss and deconstruction. It is rather an innovation: one of a cultural ensemble, of a visibility. But, is art not the invention of the visible?” [5]. His stay of ten years in Paris was a decisive stage in the development of his great work, his “life-work”, “giving his country and the entire continent a typical language” [6]. His return to Venezuela in 1964 (a time when the artistic practices fell into another dimension) should be treated as a continuation, a dialectical extension. Vigas or the complexities of exile. Going into exile for getting more rooted in pre-Hispanic cultures, in their folklore, beliefs, and popular art, confronting them with the radicalism of a contemporary artistic look” [7]. The ancestral sources as a mosaic of modernity. “I am a man of America”, he said in 1958, immediately noting that “America is a cosmos” [8]. The work by Oswaldo Vigas (alternately and simultaneously painter, ceramist, sculptor, weaver, poet), for its brilliance itself, thinks and builds its visual identity in a conscious relationship with history and by integrating a concrete dimension and a universal impact.