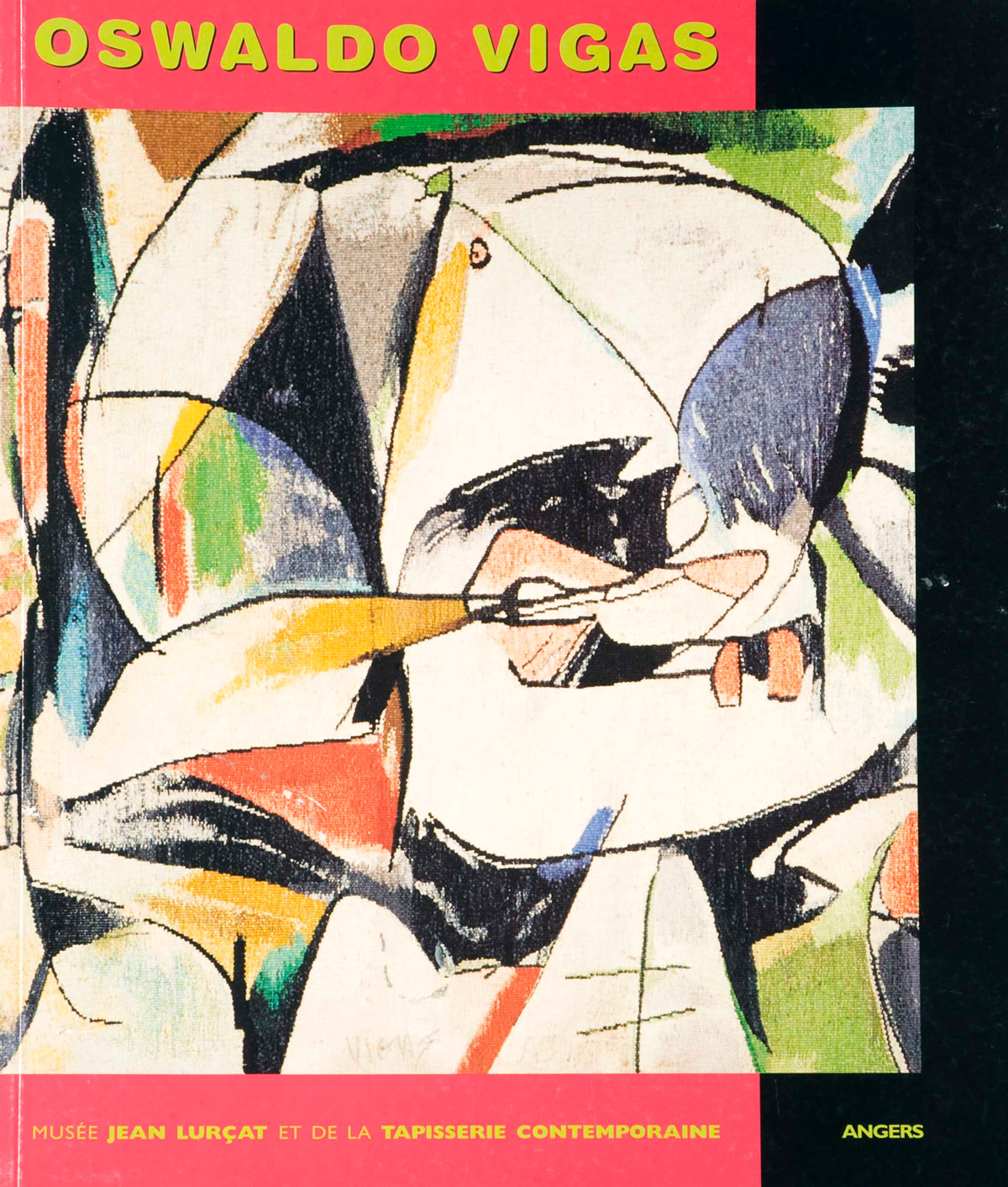

Oswaldo Vigas, Sortilèges Des Tropiques: Peintures, Tapisseries, Sculptures Et Céramiques, 1950 - 2005

Musée Jean Lurçart et de la Tapisserie Contemporaine. Angers, France. April 2005

Sortilèges des Tropiques: Oswaldo Vigas’ creation

Gilbert Lascault

Paris, April 2005

Roots

Oswaldo Vigas’ creation has its roots in Venezuela. It intertwines the modern and the archaic, the current and the hieratic, the contemporary and the original. In his frequent interviews, Oswaldo defines himself first as “a man of America” and he says: “America is a cosmos”. He senses the strengths, the deaf voices of America, and he wants to reveal them, manifest, discern and make them more understandable, conceivable. He painted the sacred and veiled aspects of America: “Our continent” (he said in 1967) “is full of dark signs and warnings. Telluric signs, magic and exorcisms are deep components of our condition. These symbols reveal something and compromise us in a disturbing world of effervescence.”

Through his paintings, sculptures, tapestries, and ceramics, through his drawings and engravings, Vigas allows us to perceive the correspondence of the elements of nature to express the harmonies and rhythms of the cosmos. He could illustrate a poem of The Flowers of Evil by Baudelaire: “Nature is a temple where living pillars / let escape sometimes its confusing words / Man traverses it through forests of symbols / that observe him with familiar glances.” Thus, the works by Oswaldo Vigas suggest the perfumes, colors and sounds of America that are in harmony with each other.

Vigas awakens, invigorates and exalts the anterior, the pre-existing. In 1998 he states: “Archaic art needs to be revitalized, for it is the most vital part of contemporary art. We need to relive it through what it should never lose: its child condition”.

Near the turbulent Orinoco, the roots are tormented, deformed, extraordinary or irregular. According to Oswaldo Vigas (1983), the trends of the continent would be “of a pre-logical, magical, mythological and anti-rationalist character.” He paints thinking of the ancestors of the Americas and the ancient kingdoms of Africa.

Vigas has always read the Venezuelan novels by Romulo Gallegos (1884-1969) that attract him: La Trepadora (1926); Doña Barbara (1929), which evokes vast savannas, alligators in the rivers, jaguars, horses and wild bulls; and especially Canaima (1935), a Venezuelan odyssey. Oswaldo Vigas paintings could illustrate this odyssey letting perceive a tropical atmosphere, one full of anguish, barbaric passions, endless dangers, of the splendor of color, an atmosphere of mixed odors, strange noises, and curses; of the heat of bodies and souls, conflicts, the corruption of society, murders and vengeance, one of Indian customs, of scattered legends. In Canaima, the jungle obsesses, captivates, worries and terrifies men.

Vigas loves the forest, like the painter Max Ernst, who also glorifies it: “The forests (...) are savage and impenetrable, black and russet, extravagant, secular, diametrical, negligent, ferocious, passionate, and kind, without yesterday or tomorrow.” The art critic Dan Haulica (1993) highlights a “natural and magical story”, the one that Max Ernst's and Oswaldo Vigas paint, that the novelist Romulo Gallegos narrates.

If Claude Levi-Strauss titled his admirable book Tristes Tropiques (1955), Vigas chooses the tropics that are never sad; these are lush tropics, endless, sometimes tragic, sometimes joyful, cheerful, always contradictory, and antagonistic. The equatorial areas that Oswaldo Vigas paints are sometimes an approach to the territories of the Cuban painter Wifredo Lam (1902-1982) and the Chilean painter Roberto Matta (1911-2002). Vigas knew Wifredo Lam well; the Cuban creates mythical figures on dark backgrounds, eerie forces and entwined lianas, jungle entities with their wings and fangs, with their defenses and their claws; with their seductive breast, sharp and acute forms, hybrid beasts, extended arms, tears, light beams, bizarre totems, unknown verticals. Born from the combination of ancestors from Europe, Africa, and Asia, Wifredo Lam proclaims himself as a mestizo and engenders a painting of various cultures, various formations, different magics; he transforms the disturbed nature. Picasso sees Lam as his “nephew”. In August 1955, Picasso also receives Oswaldo Vigas in La Californie and they are taken a photograph. Vigas is perhaps Picasso’s “little nephew”. Oswaldo Vigas often meets Roberto Matta in Paris. Matta paints force fields, opaque or transparent holes, passages, “exploding cubes”, bedazzlement, the liquidity of the night, the debauchery of the Eros ludens; likewise, Vigas evokes, in a close and very different way, sometimes dark, sometimes opalescent forests where the energies flow and fight. The critic Carlos Silva (1993) maintains that Oswaldo Vigas “is immersed in the extraordinary”, in the unusual, in what it is out of the common order. Carlos Silva considers Vigas as a “tireless explorer” of the mysteries of South America.

Witchcraft

Oswaldo Vigas’ creation would be sorcery, magic, shamanism, and enchantment. It evokes distant myths, secret or deaf rites, clandestine ceremonies, ignored liturgies. Vigas said in 1979: “A plastic expression awakens anxieties and nostalgias that are not manifested in words. These could be called “ghosts”, and they may have something to do with the religious sentiment that also includes angels and demons.” Oswaldo Vigas’ works would be in some way talismans, amulets.

In 1979, an exhibition of Vigas in Caracas gathers sixty-one works and it is titled Ritos elementales, dioses oscuros. The four elements (earth, water, air, fire) are held in deaf liturgies, undecided cults, and furtive celebrations. The divinities are dark, fearsome, secret, hidden, and somber: they are dark, crepuscular powers.

Many of Oswaldo Vigas’ paintings evoke the supernatural, the wonders: Agoríferas tropicales (1976), Arcángel (1986), Duende azul (1985), Diablo (1962), Sirena solar (1972), Sirena acostada (1994), Piel lunar (1969), Mutante (1994). Since 1950, Vigas repeatedly represents witches in painting, in drawing, in sculpture: La Bruja de la serpiente; la Niña Bruja that shakes hands with its mother; the calm Bruja del ramo; the Gran Bruja whose emblem is the turtle; the Crepuscular (1965), which is melancholic; the powerful María Lionza, which is the Dama del tapir; the Amenazadora, the Furibunda; the Dama indolente that is voluptuous and pleasantly scary; the Comedora de pájaros (1976), which is a sister of the voracious women by Picasso; Fémina disyunta (1985), which is dismembered, torn, cut; Medea erizada, jealous and vindictive; the Divinidad lunar that is a bloody Hecate; the Matadora, or the Atrapadora (1990) that grabs it all. Oswaldo Vigas’ Brujas are perhaps cousins of the women by Willem De Kooning, angry and sometimes funny, linked to the forces of nature, close to the Mesopotamian idols. Vigas’ witches, sometimes irascible, sometimes serene, announce the future, they remember the memory of the country, they predict; they can help, comfort and protect, but they can also harm, mutilate, ruin, and disadvantage. They become sibyls. They often appear in the Andean landscapes. They are the mother goddesses that fertilize and punish, deities of nature that play with life and death, with birth and destruction. According to the critic and poet Jean-Clarence Lambert (1993), Oswaldo Vigas proposes “totems without taboos”, “wild trails” of the “devouring mother.”

One of his drawing is titled el Paraíso inconcluso (1989), an unfinished paradise to a still incomplete happiness, towards a rough and incomplete Eden. For Jean-Clarence Lambert (1995), “the kingdoms are transplanted into each other: the human, vegetal, animal, and mineral kingdoms.”

Sometimes, Oswaldo Vigas proposes (as Dan Haulica says) a “theater of ancestors” hoisted on “invisible stilts”; they stand reveler and hieratic. Vigas' true historian, his friend Gaston Diehl, said that the painter is quickly passionate about the “devils” that dance before the church of Yare and about the pre-Hispanic “idols” of Tacarigua. On the front of the athenaeum of his hometown Valencia, Oswaldo Vigas creates a mural as a tribute to the culture of Tacarigua.

On the creators’ Shamanism

Vigas feels responsible, active, and conscious, but he does not want to govern. On rare occasions he has been politically active. According to him, artists have power, influence, and capabilities, but they do not want to be sovereign. Their responsibilities are special and important. In 1978, Oswaldo Vigas establishes the strange role and responsibility (partly unspecified) of the creators: “We, artists and intellectuals, are the promoters of consciousness, indispensable in all the transformation processes that have improved the human condition along history. We are “shamans”, witches or, if preferred, the gentle illuminated that in all societies are better prepared to take on a kind of moral, social, and even political responsibility that others cannot assume”. The artists subtly know the wishes of a people, their fears, and their courage. They point, they stimulate; there is an indefinable shamanism of the creators. The critic Carlos Silva evidenced the unity of aesthetics and ethics in Oswaldo Vigas’ work.

The monumental and the sculptural

Much of Oswaldo Vigas’ work consists of paintings. He also often chooses the monumental, which relates painting to architectural spaces. His search likely takes into account the Mexican “muralism” and especially pre-Columbian frescoes, the paintings and engraved rocks that can be seen in the Amazon basin in the Guayanas, in Venezuela.

With easiness, virtuosity and precision, Vigas often works the tapestry, the mosaic (for example, in 1953 at the University City and in 2005 to a bank of Caracas), and the ceramics (in 1981, a mural relief with smooth and coarse cuts). His sometimes huge works find their true dimension, their exact location. Their rhythms and cadences, their balance and bursts occupy the wall; they invade, transform and illuminate it. Their rhythms spring and glow in colorful music. Oswaldo Vigas meets again, at times, Alberto Magnelli (1888-1971) and Jean Dewasne (1921-1999), who he frequented in Paris during the fifties, and also Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944).

Made of textiles or terracotta, Vigas monumental rhythms animate and awaken the surfaces. Meanwhile, Oswaldo Vigas often seeks the sculptural. Their volumes gesticulate and grimace, move and contort; they are acrobats, jugglers, and tumblers. They are the zigotos. These volumes seduce like flowers, like “damsels”. Like Medea, the volumes agitate, they are jealous. A fearsome Divinidad lunar sculpted in clay and then in bronze has horns. Is she the terrible Hecate? The lunar divinity is two meters high; she reigns.

Efflorescence

Vigas’ creation is often efflorescence, eclosion, plenitude and exuberance. It starts. It is born. It emerges. It straightens up and rises. It is germination, a genesis. It is a source, an origin. A painting by Oswaldo Vigas is titled Biología de la Noche (1967); this nocturnal creation has been engendered by darkness. The sun brightens floating flowers and a smiling woman in Floreciente, 1967. Vigas’ visual search implies a logic, an organic development, a living arrangement, and an overflow of nature. According to Salvador Garmendia (1967), it implies a poetry, a humor without bitterness.

Teeth, claws, thorns

Oswaldo Vigas’ creation often marks, cleaves, drills, scratches, abrades, lacerates. It represents teeth, claws, fangs, pincers, needles, spurs, splinters and thorns. The forest would be a territory of the devouring and the devoured, of hunters and victims, of preys and shadows, of beasts and defeated when stalking; of traps, trickery, ambushes and threats, rumbles, terrible jumps and sometimes treacherous fights. The trunks, foliage, vines and rocks wound and kill. The jungle is the virgin forest near the equator, a region of delusions, fears, and desires. A sculpture by Vigas is called Cabeza de Guerrero (1993); it evokes a head, a giant jaw, teeth, and perhaps spikes. The forces, the violence, exacerbations and excesses are expressed through a form. In the bestiary of Oswaldo Vigas there are beasts: a scorpion, a character-bud-bug, cruel birds.

The liberation of the matter

Vigas’ creation is often the liberation of the matter, its fate. The matter and the artist fight as partners and opponents. According to art critic Robert Guevara (1993), in Oswaldo Vigas’ search “the figure is torn between arising or confusing itself with this matter and then becomes brilliant, which is itself the great character.” According to Roberto Guevara, “the matter is released”, it has been saved, changed. The artist multiplies new opportunities to make a sharper painting, a more subtle thought.

Without borders

Without cuts, separation or divorce, without incompatibility or borders, Vigas’ creation unites abstraction and figures; it prepares, combines and incorporates them. With humor, Oswaldo Vigas highlights the nuances of his procedure in 1958: “I have never been rigorously abstract or figurative. What I've always tried is to be rigorously Oswaldo Vigas.” True to himself, he escapes from any dogma, from any system. In 1982, Vigas reflects a chaotic whole, which he translates strictly, accurately. He harmonizes the complexity of the forms and forces: “Beings, plants, and vermin may have been together some time, making a unique one body. With these figures, I am simply trying to bring together what should never have been separated, to restore some balance in the disorder of creation”. Oswaldo Vigas’ creation joins the stone, the birds, the insects, the tree, and the winds together. This creation is a breath, a contained sigh, a well-ordered intensity, and a controlled power.

An interview with Oswaldo Vigas

Francoise de Loisy. April 2005

The formative years

What would you say about your childhood? Important memories...

My childhood memories are almost all linked to the image of my mother. My father was over eighty and he was blind and ill. I hardly knew him, but my mother, who idolized him, talked me a lot about him. She was 40 years younger than him. Janine (my wife) one day dared to ask her why she had married such an old man. “Because I wanted him to be the father of my children”, she replied. She had four children. The last one was born when my father was almost eighty years old. He was a doctor and a high degree Freemason, much loved and appreciated in town, but also very poor, as he did not charge sick people. On the contrary, it seemed that he gave them money when they had no way to buy medicines. Regarding my mother in those childhood years, I especially remember two circumstances: she wielding a machete that she was waving on the ground while threatening to break into our house, saying: “When I get in there, I will behead him!”, and when, during a move, the truck carrying all our furniture fell to the bottom of a precipice and my mother ran desperately trying to save some of them.

My last memories of my childhood: my mother’s voice calling me in the morning to make me go to bed, because I had spent all night studying and drawing.

The first contacts with the artistic world: your creation began early...

The first artistic activity in which I participated, when I was a child, was theater. It was in the theater, when helping to paint the landscape, that I first had a paintbrush in my hands. I was ten or twelve years old. Then, there was an exhibition of illustrated poems and my friends asked me to participate; I was competing with artists of my city that I did not know yet. To my surprise, I received the prize for best illustration. I was fifteen years old. This award gave me the courage to ask the Valencia Athenaeum for the room to make my first solo exhibit: 22 works, nearly all sold on the first day! This allowed me to buy books and help my mother, who was widowed with four children.

According to Gaston Diehl, “Oswaldo Vigas wrote plays in Mérida, in the forties.” Do you still write?

No, I did not write plays, but I wrote many short essays on politics and especially cultural essays, often published in newspapers. I also wrote poetry, which has never been published; I have enough to publish more than one book. Unfortunately, they have not been translated into French. I am like the artists of the CoBrA group: all of them wrote poems.

1945, Mérida, the medical school... You got to the end of your studies while painting and actively participating in campus life.

Yes, I studied medicine; I finished my studies in Caracas at the Universidad Central in 1951 because I always finish what I start. It was with painting that I could pay for my studies, but I knew that I would never practice medicine. Of course, when I arrived in Paris, a year after my graduation, the friends who had no money to go to see a doctor visited me so I gave them medical advice or so I injected them. At first, I worked as a foreign assistant at the Necker hospital for sick children because I had made a course on pediatrics in Caracas, but I left all that very quickly and dedicated myself only to painting and a lot of cultural activities.

1949, Caracas, member of the Free Art Workshop... Where do you place yourself in relation to other artistic movements in Venezuela and in Europe?

The Free Art Workshop brought together the artists who did not want to cut ties with their roots, unlike the other group that was later formed in Paris and that was called “the dissidents”, who wanted to make a “new” art without any connection with the past of their country. These are the artists who, upon their arrival in Paris, enrolled in what is pompously called “Abstract Art Academy”, created by Vasarely, Dewasne and Pillet. I think many artists of my country sacrificed their talent in search of an “internationalist” fantasy. When they came to my studio at 33 Dauphine Street and saw what I was painting, they always said “Vigas, you're in prehistory”. I made this observation my flag!

When you were very young, you received an artistic recognition. In 1952 you already had a first major retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Caracas. Are you aware that you have an extraordinary trajectory?

Yes, I have been aware of this for a long time, even since my childhood. I was very fortunate. As for my great success in 1952, I received the national award and all the other major awards at the time, a year after having receiving my medical degree. Let’s not even talk about all the enemies I made. At that time, I was the great “star” of the arts and paid a high price, because, of course, many never forgave me.

Portrait of a man

Friends, companions...

I have always been very outgoing and easy to make friends; almost always they were recognized and older than me. For example, I used to visit Fernand Léger in his studio on the street where the Grande Chaumière is, or in his home in Biot. Max Ernst and his wife, Dorothea Tanning, were always the first to come to my exhibits and they used to visit me in my studio, especially Dorothea. Alberto Magnelli lived in Alesia; he was a wonderful, friendly, sensitive and humble person. I loved him very much. Picasso would have liked me to be interested in his daughter Maya. Wifredo Lam is a separate episode. I was like a brother to him, a confidant whom he constantly asked for advice, especially for his affairs of the heart. We saw each other every day. I remember when he came to Paris with his wife (his current widow, Lou) after a long absence (I think he was in Norway). He came to my studio at midnight to introduce me to Lou and secretly asked me what I thought, if I liked her! You can see us again in a photo of 1980, two years before his death. He was already paralyzed. We cried together.

I was less close to Matta, but we still were friends. When he arrived from the United States after the war, it was me who introduced him to the committee of the Salon de Mai. He always remembers the boxes of whiskey I sent him for Christmas when I was cultural attaché of the Venezuelan Embassy in Paris. I was very sorry to see him in Caracas about ten years ago, being very “diva”, capricious and rude to the people trying to approach him.

An active and committed intellectual

The galleries... In Venezuela: Antañona, Durban (Caracas). In Paris: La Roue, Neufville, etc. What contacts do you have with them today?

I trust my paintings to the people I love and appreciate as friends. In Caracas, there are two galleries with which I currently work: Ascaso and Medicci. A long ago, I cut ties overnight with the Durban gallery -the one which took over my work for some years- because I discovered that the owner saw me only as “a number”. The next day I took away all the works that I had given them.

As for the galleries in Paris, the La Roue Gallery was installed in the Latin Quarter, near the boulevard Saint-Germain. The owner was interested in my work, so I exhibited there. The owner of the Neufville Gallery was not specialized in Latin American art. In fact, when I lived in Paris, I cannot remember any gallery specialized in Latin American art. Personally, I think I had to do with what I got during my stay in France. I also blame myself for having cut ties, upon my return to my country, with a lot of people, distributors, critics, etc., that were interested in my work. But it was another time in my life and I usually give myself completely to what I do, wherever I am.

The traveling, the long stays...

In France from 1952 to 1964, coming back to my country in 1957-1958 and occasionally in the eighties. In Spain: 1953, 1957. In Latin America: Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador and Mexico in 1976, the Andes in 1984. The United States: 1958, 1971-1972.

Can you tell us about some of these experiences, the most valuable to you, or memories that have marked your creation?

From all points of view, my stay in France for more than twelve years has been essential in my life as a man and as an artist. I learned to know and love my continent when I saw it from afar, when I met all these great figures that I frequented in Paris and that I would never have met if I had stayed in Caracas. I met writers, poets, painters and sculptors, politicians, musicians, and even “folklorists” of the various countries in South America. The list would be too long: Carpentier, Neruda, Octavio Paz, Alberti, Picasso, Violeta Parra, etc. Not to mention my great loves, which were very important in my life, it was Janine who, from a certain point, took the whole place.

As for my travels in Spain, the critic José María Moreno Galván, eternal prisoner of the Franco dictatorship, was the person I met during my first stay in Madrid and who put me in touch with the leading figures of El Paso and Dao al set. Then I kept meeting Saura, Tapies, Canogar, Pablo Serrano, Juana Francés and Tharrats, who has written several times about my work. I saw them again during my visit and exhibition in Madrid in 1957, and later, when many of them were refugees in Paris.

My travel from 1971 to 1972 to the United States, invited by the State Department (which, by the way, was very surprised by the difficulties I had every time I wanted to go there), was a feat because, in a very short time, I had to visit over 15 major cities and some fifty museums. I also met many personalities, there were interviews and worldliness every day! One of the saddest and most consistent findings was that, with rare exceptions, Latin American art was completely absent from most museums, with the exception of New York, of course. But New York is far from reflecting the United States in general.

My travels throughout Latin America left me, in the first place, memories of the friends I met there. Humans are usually more important than landscapes or geography, but how can I forget the crossing of Lake Titicaca, Cuzco, Machu Picchu (where I got lost in the ruins), and many other wonders, like the Gold Museum of the very interesting city of Bogotá, and personalities like Guayasamín in Quito, Obregón and Grau in Cartagena, Szyszlo in Lima, etc.?

Official responsibilities...

Cultural manager of the Venezuelan Embassy in Paris (1962). Curator (Venice Biennale in 1962, Latin American art in Paris, in 1962). Correspondent for the Capriles group, 1962. Director of Culture at the University of the Andes, 1966. Organizer and coordinator of the first international music and film festival (the first Latin American documentary film festival) in Mérida, 1968. Founder of the Museum of Modern Art in Mérida, 1969.

What does enrich your creation?

All the things you have mentioned are indeed aspects of my personality. For a long time, I took all of these things at once. They stimulated my creativity. I kept painting, for example, during the five years I spent in Mérida as Director of Culture at the University of the Andes, organizing the operation of all the art schools, the programming of concerts, plays, exhibits, festivals, etc. I've always been like that: in Mérida, during my medical studies, then in Caracas, and in Paris, where I was a true leader of the Latin American activities of the time. This continued after I moved to Caracas, where I was a member of all the committees in charge of art and culture in general. Only in recent years I stayed away from public and controversial activities, not only because I wanted to or because my strength declined and I preferred to keep the focus on my creation, but also because of the turn taken by the political events in my country. We are living a moment of true pre-logical madness, irrational and interesting to study from a psychological point of view, but very bad for the activities of the spirit and where I have nothing to seek or win.

Official recognitions, awards, decorations, exhibitions... And recently the prestigious Latinidad Prize (2004). Does that seem paradoxical? How do you live it?

The only thing missing in my resume is that I have never been in jail, although several times I was about to be. Now it is too late, because they do not put people of my age in jail! Regarding the Latinity Award, my name was proposed among others and all the ambassadors of the Latin countries voted for mine. They must have had their reasons, right? Also, here it is now recommended to choose an artist to avoid delving into politics!

The tapestry and the wall desire. When were they born?

It was the proposal of the architect Carlos Raul Villanueva to make mosaic panels in the University City of Caracas in 1953 that awakened the “wall desire”, as you have called it. As for tapestry, there was also the proposal of another sponsor, Ana Teresa Dagnino (a high society Venezuelan lady who painted and was eager to weave and exhibit her works, but with renowned painters, as was my case and Humberto Sánchez Jaimes’), who put me on that road and who allowed me to make my first sketches, which were taken to Portugal, where they wove my first works in Vitoria and Portalegre workshop.

The first tapestries...

The first three were woven at the Vitoria workshops in 1971-1972. Anfión II, woven in Mexico in 1972, is long lost and everything around it was so mysterious that we decided not to include it in the inventory of tapestries. Sirena Solar, to be exhibited in Angers, was woven at the Portalegre workshops in 1971 (its name was changed because at first I had titled it Señora de Los Fuegos crepusculares). Then, with the assistance of Gaston Diehl, Ms. Dagnino spoke to Saint-Cyr workshops, where La Bruja Azul was woven in 1971. Then I made tapestries in 1972 (Geometría de un personaje) and 1977 (Gran ancestro) with the Telarte workshops in Madrid. Meanwhile, and sometimes at the same time, P. Daquin and C. Legoueix workshops made my tapestries. The last woven by Daquin in Saint-Cyr in 1985, was the small Hermafrodista, which “lives” in New York. Selváticas was woven at the School of Fine Arts in Angers, under the direction of Pierre, the then professor of the textile and tapestry workshop of the school in 1994.

In 1992, Legoueix workshops (M. Legoueix was already dead at the time) weave the second version of Chamánico and Aguilador. It is also during this year when I get to know Peter and Frédérique Schönwald, whom I trusted my last five tapestries.

The Saint-Cyr workshop experience. Working with Pierre Daquin and Camille Legoueix...

Gaston Diehl, one of my dearest friends, advised me to work with Pierre Daquin and Camille Legoueix when, after the experiences in Portugal, I wanted to weave my works there. With Pierre Daquin and his team of that time -I especially remember Chantal and Thierry- the harmony was immediate and Pierre's advice was very important for me, since I had little experience in that field. Pierre is not only a weaver, he is also a creative and an intellectual with very specific personal ideas. Pierre Daquin made excellent personal works in “textilería” (I know this word does not exist, but he will introduce it). That does not prevent him from being an excellent translator of my work, and I also believe that he was interested in it. He was able, at first glance, to see what a small sketch would give me and to make me correct the defects that it might have during its manufacturing. We held long conversations and our meetings were always productive. I think he was a great weaver.

As for Camille Legoueix, he was something else. He was not a creator, but he certainly was a great craftsman, often called “the master weaver of France”. He was also the head of a big “company” in which several great weavers worked. We cannot ignore that he was one of the most important collaborators of Jean Lurçat. I remember him showing the magnificent Lurçat tapestry he had in his living room with such emotion. I was so excited the day he told me he was interested in my work and that he would love to do more using natural wool with no dye. I was very fond of him and his family, especially of his wife, who was his assistant, too.

Unlike the movement of “new tapestry”, which also exists in Venezuela, you are a painter that has been translated into wool. Do you agree with this definition?

Yes, I am a painter who has been translated into wool. I discovered with pleasure that tapestry reveals other aspects of my work. My painting is rough, not complacent; tapestry apparently makes it more enjoyable and that does not seem bad to me. I am pleased with all the translations that have been made from my sketches to tapestries.

Without speaking of the first tapestries, because I did not follow their making at all, the three weavers who worked for me were Daquin, Legoueix, and now the Schönwald from the Atelier 3. Each in their own way, have made interpretations of my work that I always have been satisfied with. My tapestries are and should be a continuation of my painting. When I make a sketch for a tapestry, I am basically a painter. One of the main features of my work, as it generally is for all contemporary Latin American art, is continuity, never rupture. When making my sketches for tapestries, I never sought to break with the rest of my work. For example, I have never used wool to make sculptures. I was never interested in it.

*The “new tapestry” takes place in the second half of the twentieth century, thanks to the innovations of some avant-garde artists (Grau-Garriga, Abakanowicz, Olga de Amaral...). This international movement is characterized by a factual and aesthetic rupture with the so-called “classic” and mural tapestry in the 1950s (of which Jean Lurçat is one of the best representatives). The artist often creates his own tapestry putting an end to its intermediaries. The tapestry can be three-dimensional, adopting, most of the times, an abstract language that highlights the materials.

Ceramics or the pleasure of the matter

When in 1980-1981 I made the mural on the facade of the Valencia Athenaeum (three by ten meters) with sandstone slabs carved with reliefs, I had no idea of any ceramic techniques. I was assigned an assistant who knew about traditional ceramics and who introduced me to it, but I realized that what I wanted to do had nothing to do with what he knew. Thus, I invented my own techniques and that is how all these pieces were born. They exceed the total number of two hundred.

All this in the huge industrial company Cerámicas Carabobo in Valencia, sponsor of the mural, which put at my disposal the facilities, materials and staff when needed. So all my ceramics were cooked in large industrial furnaces, where I got my pieces to hundreds of other destinations, on sale in supermarkets... with all the risks that you assume! The sandstone slabs that I would exhibit and the mural pieces were baked at high temperature. These experiences lasted more than a year -the time for the completion of the mural. I was still very ignorant of the traditional way of making ceramics. For example, I used the pure oxides, sometimes diluted with water and often with paraffin, which facilitated the brush stroke. I worked with clay from Carora (a Venezuelan region that offers a particularly desirable clay for its finesse and quality).

Then you invented your own techniques, your own “oven”. Could you not have an intermediary to work according to your designs, like in tapestry?

An “intermediary” in ceramics is unthinkable. Drawing on a plate or doing it on paper is exactly the same. Nobody can do it for me. For reasons of time and because I wanted to make the most of this new experience, I worked on existing forms. For the same reasons, the opportunity to make my designs in ceramics presented itself without me having sought it, and I used projects -some quite old- for which I had never made a painting, for example Cabeza Vegetal. On the other hand, there are many ceramics which designs were made without previous projects, such as Cabeza Marrón.

Has pre-Columbian ceramics influenced or nurtured your artistic creation?

There is a “connection” to pre-Columbian art in all my work. It is another aspect of this historical “continuity” between our past and our present, because I am convinced that, as I heard André Malraux say one day: “What comes out of nowhere, is going nowhere”.

The sculpture or the three-dimensional experience. Date of the first sculptures?

I have made sculpture projects since 1970. I made them in breadcrumbs, folding cardboard, papier maché, etc., but it was only in 1981, after my experiences with ceramics, that I learnt how to make sculptures. It was in Mérida where I first melted bronze and I kept melting the new ones (at Fundición La Fortaleza, with Mr. Adán Vergara). The most recent is La Dama de Tabay. I am currently working on my projects made in breadcrumbs in the 1970s with another smelter, who is not so far-away as that in Mérida. The more abstract are the most beautiful works. He also has what I call “my multiples”, because I made 20 copies. He will make 5 pieces to be exhibited in Angers: Novia coloniera, Muñeca coloniera, Rétrodicente, Ente mágico and Busto I. For these, I worked the sketch and the mold with a smith and then I covered them with bronze in the city of Barquisimeto (with Ricardo Roa).

How does the three-dimensional contribute to the direct work with clay?

People on that field have often told me that it was rare that a painter made a sculpture so successfully. I have always said that a painter who does not get his hands dirty is not a painter, and that is confirmed even in sculpture. I love getting covered with dough and I wish I could work both sculpture and painting. Unfortunately, it is much more complicated, especially because of the foundry. When I am modeling, I do not think in painting at all; I immediately see the image in three dimensions.

Large sculptures and “jewel” sculptures. How big is the biggest? How small is the smallest?

My biggest sculpture is Gran Alma Mater, which is 3 meters high. I have sculptures of various sizes, such as Gran Matadora, measuring more than a meter, Posante, of 57 cm, or Novia coloniera, which is only 25 cm. I have also made small silver sculptures that can measure 12 cm, as Figura sentada, and jewels like Wawaki. The work is just as difficult in big and small pieces, but I like to experiment.

About how many sculptures have you made? All of them are made of bronze?

Yes, all bronze, except the small ones made of silver and the jewelry. They are twenty in total. As for the bronzes, there are now 33.

When you make sculptures, do you work painting at the same time? Drawing?

Yes, everything at the same time.

The facets of creation

From drawings to pictures, from sketches to the finished work, the ways of creation...

I make my sketches anytime, anywhere: when I am talking on the phone, in the restaurant on paper napkins, in the subway on metro tickets, in trains, planes, etc. That is the real moment of creation for me, of pure creation. Then, reason intervenes and it makes me choose a sketch instead of another to transform it into a painting, a sketch that undergoes the necessary changes to become a painting. Sometimes there are not many changes, but sometimes it changes completely.

The notion of pleasure in creating

Is the material used (ink, charcoal, oil, dirt, wool) just a simple means or does it give you pleasure to express? Intellectual pleasure, physical pleasure...

There is no difference between all the materials that you name. There is always the “pleasure” to create, which often turns into anguish and pain.

The themes

Cycles of works? Recurring themes, for example, crucifixion, commemoration (e.g.: Bolívar.), tribute to friends...

That depends on the moments of existence, I have no line of evolution. As Marta Traba said, my work is an eternal going back to go forward. I do not think going back is more important than going forward or the other way around. Yes, there are recurrent themes. The most important theme of my work is the woman, as it is the image that most interested me in my life, whether it is the mother, the sister, or the lover. Always the “Mother Goddess”, terrible and castrating, or protective and welcoming. This can be a way to exorcise its importance, but I do not trust this psychoanalytic interpretation. It is true, crucifixion is also a recurring theme in my work. I am interested in it, but not from the point of view of the religious practice. “Religious” comes from the word religare, which means “to unite what is separated”. That is what I am interested in. This is also the function of art, which is why all art is religious.

A “personal” mythology linked to that of Latin America (witches, beings...)

Yes, my work would be a bridge between our time, our past and our future, like putting one foot in the stirrup of the past to move forward. Also, as I dared to say in 1982: “beings, plants, and vermin may have been together some time, making a unique one body. With these figures, I am simply trying to bring together what should never have been separated, to restore some balance in the disorder of creation”.

What cultural particularity of Venezuela influences your work?

To answer that, I'll tell you what I consider my “credo”: “Our continent is full of dark signs and warnings. Telluric signs, magic and exorcisms are deep components of our condition. These symbols reveal something and compromise us in a disturbing world of effervescence“ (Mérida, 1967).

“Entes”.

Frédérique Bachellerie, Peter Schönwald, Atelier 3, Paris. May 8, 2005.

We met Oswaldo Vigas and his wife Janine in 1992 through Pierre Daquin. They came to our workshop in Paris, with their arms full of books, exhibition catalogs, prints and drawings, and we were immediately plunged into the joyful world of the Entes.

Entes? They are the dynamic beings, fighting warriors often appearing in pairs, occupying all the space. Oswaldo granted us the privilege of choosing among his oils and gouaches the subjects to weave. We had enthusiasm in common.

Since the founding of our workshop in 1972, we weave for artists starting with one of their works, those that have not been developed specifically for tapestry. We believe that the design freedom of the artist remains whole in this way. For us weavers, the transposition of the painted work into tapestry follows: enlarging the original using a slide, drawing the tracing, choosing colored textiles... We feel attracted to these subjects with few colors, and this accentuates the monumentality of Vigas’ composition. This limitation of colors and this exuberant presence of imaginary “entes” pushed us to freedom. Firmly identified by a powerful black drawing, we wove these forms with unusual materials: cloth strips called lirettes, or paper mixed with cotton avidly “eating” the surfaces, giving volume against stiff and flat linen supporting the whole.

The first tapestry, Canaima (792 x 352 cm), was exhibited in the castle of the Adhémar in Montelimar, 1994-1995: Tapisseries d’aujourd’hui sur murs d’autrefois.

The second tapestry participated in the exhibition of Atelier 3 in Artrium (Lyon Auditorium) in 1997-1998. Three new tapestries have come up since then, bringing us closer to the powerful and ingenuous world of Oswaldo Vigas.

We are pleased to participate in this exhibition at the Musée Jean Lurçat et de la tapisserie contemporaine, in Angers, a major center of textile art.