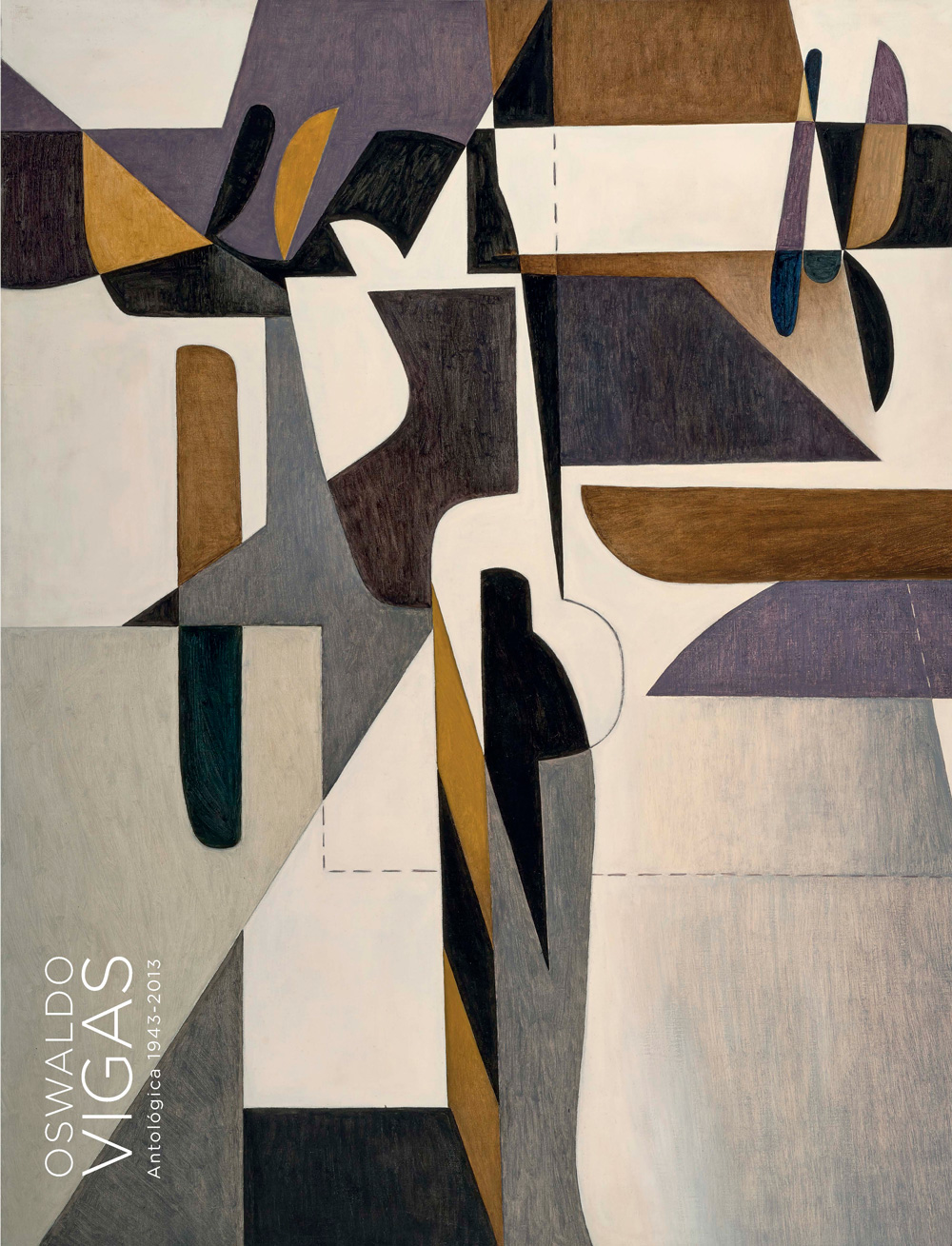

OSWALDO VIGAS ANTHOLOGICAL 1943 – 2013

Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil

April – July 2016

Reencounter and revisit

Oswaldo Vigas, when he was 27 years old, was a promising Venezuelan artist that showed three paintings, as part of his country’s delegation, at the II São Paulo Art Biennial. Such event was set forth to celebrate the 4º Centennial of the City of São Paulo between December 1953 and January 1954, inaugurating the Pavilhão das Nações and the Ibirapuera Park- both designed by Oscar Neimeyer and his team.

Juan Röhl, Venezuelan delegate before the II Biennial, welcomed Oswaldo Vigas in the catalogue, saying that “Vigas is gifted with a sensitive and beautiful intuition in his compositions; it shows a sensual richness in his palette.” In the early 50’s, the young artist was recognized for his work, he was awarded for different artworks in his home country- during this decade, the artist also moved to Paris; where he lived twelve years. In 1955, Vigas participated in the II São Paulo Art Biennial with two paintings; this participation was going to be, possibly, the last appearance of the artist in Brazil.

The appreciation of Mujer (1952) and Yare (1952), two of the paintings showed in the II Biennial, could be interpreted as a reencounter of the artist with São Paulo. In a space not far away from the one where his artwork was shown in 1953 (nowadays, known as Pavilhão Armando de Salles Oliveira), the institution kept the art collection of the first São Paulo biennials; also, the Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo was sheltered within the building where the celebration of the 4º Centenary was held- the Pavilhão da Agricultura.

The Venezuelan artist was ignored by Brazilian culture; notwithstanding, the artist’s intention was aligned with the Latin American universe of the 50’s and 60’s- period of time in which Brazilians shared concepts. Vigas was on the artists that participated in the experience Synthesis of the Arts, conceived by Carlos Raúl Villanueva, Venezuelan architect that designed the extraordinary campus of the Universidad Central de Venezuela; recognized by the UNESCO as World Heritage. Integration of the Arts was another term used for this debate, which was also called by the Brazilian Lucio Costa, differing from those concepts, as Communion of the Arts. Paraphrasing Damián Bayón, in such debate, Portinari, Di Cavalcanti, Clóvis Graciano, Lívio Abramo, Alfredo Ceschiatti, Athos Bulcão, among others; aligned with Diego Rivera, Mateo Manaure, David Alfaro Siqueros, Oswaldo Guayasamín, José Clemente Orozco, Wilfredo Lam, Miguel Alandia Pantoja, José Chávez Morado, and Oswaldo Vigas in the rhythm of a “Latin American plastic adventure.”

More than a reencounter of Vigas with São Paulo, this is about the encounter of São Paulo with a great Venezuelan artist who is practically unknown in our cultural spectrum, whose retrospective rescues his role and his importance not only for Brazil, but for Latin America and the rest of the world.

After a journey through Lima, Santiago, and Bogota, the Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo receives with great satisfaction the retrospective Oswaldo Vigas Antológica 1943-2013. We would like to thank the Fundación Oswaldo Vigas and the exhibition’s curator, Bélgica Rodríguez, for showing the entire corpus of the great Venezuelan máster to the Brazilian public.

Hugo Segawa

Director MAC USP

2014-2015

Oswaldo Vigas’ artistic studies and career

Lisbeth Rebollo Gonçalves [1]

It is the first time that a Brazilian museum displays an Oswaldo Vigas’ exhibition. This event shows spectators the Venezuelan plastic artist’s career and the insights of the production of this expressive Latin American artist. Within this region, Vigas is one of the constructors of a unique sense of esthetics, in which memories from the past help in the pursuit of the new languages of the art.

Firstly, Oswaldo Vigas studied arts in his home country; and then, he had an important experience in Paris (where he lived from 1952 to 1964) - this city was considered the center of the arts during the 50’s.

The dynamics of his artistic journey placed the artist in close contact with the modern art of the 20th century; thus, Vigas was able to be closely influenced by the newest esthetic aspects of that time. This experience was also lived by other Latin American artists, who were part of the same generation of modern artists, among which we can mention: Torres Garcia (Uruguayan), Wifredo Lam (Cuban), Roberto Matta (Chilean), Fernando de Szyszlo (Peruvian), and Antonio Bandeira (Brazilian.) From the influence lived in Paris, these artists gained important experiences that later were going to be important for the history of art of their countries.

In the middle of the French artistic effervescence, Oswaldo Vigas studied, extensively, the problems of the plastic arts. He restudied the understanding of plastic space in painting and understood art as a language, without putting aside important cultural references of his culture of origin. During his artistic career, there were many times when tradition caused an immersion in a mythical universe which joined with modern premises- this joint was essential and one of the key points to understand Viga’s career, where tradition and rupture coexist.

Looking for the essential expression

In 1953, during the artist practices, Vigas started to worry about esthetic language matters and started to debug better his painting. At this point, lines and plastic space structure caught the artist’s attention. In that same year, Vigas had an exhibition in the II Sao Paulo Art Biennial; such event was held to celebrate the IV Hundredth anniversary of the foundation of this Brazilian city. Also, in 1953, Vigas attended the IX Salão de Maio de Paris, at the Museum of Modern Art of Paris; to such event there were abstract artists invited; for example: Atlan, Dewasne, Poliakoff, Soulages, Vieira da Silva, among others.

It could be said that Vigas was being reaffirmed within the worldwide group of the arts. In Oswaldo Vigas’ case, the 50’s were important for his work; the artist reached very important achievements and improved his career. In 1954, Vigas attended the XVII Venice Biennale, where he showed three of his artworks in the Venezuelan Pavilion, which was inaugurated in that same year in the Giardini. Vigas also displayed an exhibition in the Pan-American Union; he was part of the work organized by the Smithsonian Institute, which was shown in different American Museums.

Due to the artist’s studies of abstract art, innovation results came out of his work and reflected upon the comprehension of the plastic space in painting.

During his production period, canvas showed dark colors and thick and black outlining. Although the dialogue with geometrical abstraction is seen, the artist used grays, ochers, and greens colors with an important symbolic density. During that time, something similar happened to other Latin American artists like Wilfredo Lam and Roberto Matta; or the Brazilian artists Aldo Bonadei and Burle Marx. An exploration field of the tensions between abstraction and figuration was defined as inevitable for these artists, in their pursuit of esthetics. They plunged into the challenge of experimenting with abstract art; whose origin is European. Those artists focused on studying lines and space structure.

In the artworks of that time, the importance of the lines, its musicality, and the conviction in the gesture of the artist could be seen; building together the composition and defining a dynamic space, where the delicacy of the ochers is seen in a broad range. That type of artwork could be defined in its core as a musical painting. In that moment, the urgency of a strong poetical density could be appreciated in the artist’s work.

If color fulfills its important role in art, lines are highlighted along the process of elaboration of a composition. Color has a functional role, it contributes to balance and movement sensation in an artwork. Lines create shapes and outlines, but also defines some vibration; lines cross vividly the canvas with an abstract concept of organization, but it shows some suggestion of the perception of reality seen throughout the name of the painting. The names of the paintings give spectators the exercise of creating symbolism; therefore, Vigas’ work is fully mature.

Painting and previous experience

When appreciating the artist’s work, an esthetic tension point between abstraction and figuration can be identified; such point is the driving force that generates shapes. Thus, dimension and the artist previous experience seem to be related.

From the artist’s composition work, where pictorial space is fundamental, the artist shifts from elaborations, where formal matters continue to be present and important, but the surface of the images make spectators think of ritualistic characters of ancient origins.

That movement, a unique esthetic way of creating, is a property that characterizes the identity of the artwork of several Latin American plastic artists. Among the plastic artists that use such shifting, we can mention Lam, Matta, and Torres García. Also, this characteristic can be identified in the work of well-known writers- like Carpentier and García Márquez, among others. The use of metaphors refers to an otherness that is maintained throughout time.

Seeking concept

In the early 60’s, a stage focused on concepts and full of gestures emerged from the Oswaldo Vigas’ work. In the artworks produced in this stage, imagination turned into a vital impulse. The artist was researching on the dimension of space, which is very important in the abstract art; where space and time are related and a path that leads to an absolute truth is open. In this stage, gesturing is valued in plastic creation.

Something similar to what happened to Wols and Atlan is seen in Oswaldo Vigas’ work. According to Vallier2, technique is the driving force of images. Material opens space for imagination games; which could be intentional. During the artist’s experimentations, the relation to painting is phenomenological. According to Lyotard3, this is the energy’s driving force; a libidinal pulse. An energetic dynamic that does not follow the reading codes of images.

Shaping career

The symbolic archetypes are seen when shaping; but also, these are conceived as challenging aspects and also part of the artist’s shaping career for those who appreciate his work.

In the artwork produced during this period, animals and plants constituted part of Vigas’ work. During this period, Oswaldo Vigas went back, once again, to his cultural origins. Nevertheless, during this period, the artist’s work suffered changes in its formal elaboration; backgrounds were freely painted with intense colors (red, yellow, blue, and black), shapes were fragmented, and the importance of the line was reaffirmed along with the importance of color and matter. In some of his work, Vigas leans towards experimenting with more geometrical shapes; building images throughout fragmentation.

Tridimensional career

Vigas’ tridimensional career is seen in the sculptures that the artist made during the 60’s and later, in the 80’s and 00’s. In his sculpture, spectators are driven into an oneiric world, filled with extremely expressive images.

In the artist’s tridimensional work, it could be seen once again the importance that material and textures have in the language of plastic arts.

Vigas’ sculpture career establishes a significant dialogue with pictorial expression. Sculpture and painting became a dynamic field which is closely related to plastic arts. This dynamic field fluctuates in between sculpture and painting and constitutes a formal dialogue; which emerges as a “new archetypal figuration.” Would those be ritualistic images? The artist seems to invent and reinvent new esthetic dialogues in the ritual of limitless creation; which was always part of his artistic career.

Oswaldo Vigas

Bélgica Rodríguez

Oswaldo Vigas discovered the thresholds to access the mysteries and secrets of other dawns and thus began his adventure with art at a very young age. Vigas was blessed with a special, innate talent and realized, amidst the shadows of the trees and the words whispered by the breeze that lulled the waves of the Cabriales River in his native Valencia, that he had a hidden vocation. He was born on August 4th 1926 into the open spaces of this important provincial city, which would gradually awaken his spirit and taste for beauty: painting was his destiny. His early inquiries opened his spirit to the creative “phantoms” that propelled him towards out of the ordinary revelations. His first Baroque style compositions Tetragramista II and Composición IV (both from 1943) feature Cubist-influenced fantastical shapes and figures based on his memories, but also are also testimony to his self-taught lessons in art history. He finished his primary and secondary education without losing his interest in art and without his commitment to his illustrations, drawings and collages waning. He did not attend any art school, but graduated in Medicine from the Central University of Venezuela instead, although he did not practice because he decided to dedicate himself to art.

With a clear idea of his goals, he found the way to develop his own style within the figurative painting that was being made in Venezuela during the fifties. His fascination for local pre-Hispanic culture led him to travel throughout the country. He discovered and studied the iconography of these artistic manifestations; the female figure of a flattened Venus with coffee bean eyes made a considerable impact on him and he borrowed features from her that he later presented in the figure that has become his trademark: the witch figure. “After flattening the head, I stretched her neck out, made her ribs visible, and removed her fingers and toes. I revealed the bones in her arms, making branches, shoots and tropical fruits grow all over her body and so that no animal kingdom would feel left out I covered the Witches with rust, crystals and all the over mineral leftovers that fall from heaven (…)” (Exhibition catalogue, 1996, Casa de Las Américas, La Habana, Cuba). Vigas approached the telluric cosmology of these ancient cultures and the mysterious ancestors present in Latin America. As he delved into their beliefs, he discovered the image that represented them, their surroundings and concepts, and used it to create an entire subject matter. Vigas’ witches are a common topic. The artist encountered a path and left serene and turbulent footprints upon it, which have secured him a long and luminous journey.

Entering Oswaldo Vigas’ studio is like going into a world full of memories, references to Venezuelan and Latin American history of art, presences and absences, pre-Hispanic sculptures, and a grand piano. There one finds painting after painting organized chronologically, ready to be exhibited in an exhibition. These paintings, of course, belong to Vigas, who has taken great care to store his own museum of works dating from 1942 until today. Paintings, engraving, tapestries, drawings, pottery and sculpture are testimony to a life completely dedicated to art. He barely rests or stops, but when he does Vigas uses the time to read and re-read the key texts that refresh his memory and knowledge base. He also speaks and shouts in defense of a creative world that belongs exclusively to him: “My work is neither meticulously abstract nor figurative. I have always tried to be meticulously Oswaldo Vigas”. His images are immediately recognizable due to his coherent personal style and personal philosophy toward life and art: “I am lightning and thunder” is the way he describes himself in a debate on art published years ago in a local newspaper. Art’s ability to consecrate and its multiple roles are pillars in his beliefs and he focuses specifically on the autonomy of form and emotions as art’s core. The origin and nature of his work is the beautiful product of his creative life.

A relevant aspect in Vigas’ work is his connection to certain principles of direct perception and the transformation of fluid sensations into objects, whereby the painting acquires an immediate presence, while it also representing a past by association. The witch figures change every decade: in the sixties they were aggressive, violent and also kind. They were closer to the figurative expressionism of the historical avant-gardes in Europe and New York. The artist was immersed in a violent world that was bound to his personal beliefs about figurative art, which posited a transgression that sought to undo the predominance of the figure as the main subject matter. His work’s formal logic thus responded to the union of symbolism and iconography in a global village full of human problems.

Vigas’ painting is well known for its careful formal practice, dominated by thick black lines that provide the outline of his figures, or thick geometric lines that delimit and organize his abstraction. Vigas bases his works on a previously formed idea that naturally changes during the process of painting; he transposes the idea onto the canvas with precision. His drawers are a treasure trove of thousands of sketches, drawings and diagrams that he often revisits to make different types of work: painting, sculpture, tapestry or pottery. The sketch is held by a hand that seems to randomly move over the canvas, paper, clay or other material. However, his actions are not irrational; on the contrary, they obey a careful and rational plan. The final result displays a freedom in the strokes of the thick or thin brushes he uses skillfully and confidently. Vigas defends the freedom of the act of creation and the spirit in order to engross himself in his work in full knowledge of his goals. Among other things, he is interesting in sequences and a meaningful combination of form and content that is ultimately closely linked to the sense of beauty that his works irradiate. His works transmit a particular type of beauty that does not only aspire to being contemplated, but also to materialize a human emotion, which therefore means he considers aesthetics in terms of the context he represents with such mastery.

Several themes could be identified in Vigas’ artistic career, but the female figure of the witch is without a doubt the subject that predominates throughout his different periods. He began with La gran bruja (1951), which earned him the National Fine Art Prize in 1952, which positioned him firmly in the Venezuelan art scene at a time when its incipient modernism was pursuing the universal language of geometric abstraction. He became involved in the creative tumult of the well-established collective, Free Art Workshop in Caracas. By that time, Vigas had simplified his abstract or figurative forms and the structure of his compositions. The female figure was situated on a backdrop of flat colors and her body and expression were given a geometrical form, using strident colors and shaded lines progressively in order to create profoundly symbolic and iconic images that respond to a natural energy that permeates his work and its mysterious atmospheres. The latter is constantly present in Vigas’ various subjects, which at the start of his career were fantastic, abstract, organic and geometric, and which in following decades sometimes included landscape as well.

In the fifties, Vigas turned briefly towards geometry and produced intensely beautiful and powerful art works. He made a series of geometric abstract works entitled Figura descompuesta (1956) that, despite dividing the composition into rigorous geometric planes, are striking because they managed to retain the sensuality and organic aesthetic that characterize his painting. He was invited by Carlos Raúl Villanueva to take part in the project for The Integration of the Arts in Caracas’ University City, where he designed four abstract murals using Venetian mosaic. Vigas rapidly went from one stage to the next. In the sixties he turned to informalism, a style that appeared at the time in Venezuela and was adopted by several important artists by virtue of its iconoclastic and irreverent attitude, its rejection of figurative art and, more specifically, geometric abstract art. Informalism took up much of the sixties. Vigas adopted its codes, which were a novelty at the time, without distancing himself completely from figurative art. Much of the work he made at that time reveals hidden sketches that resemble mysterious ghosts hidden within the exuberance of his sweeping brushstrokes. A further symptom of figurative art resides in the title’s reference to subject matter, which also refer to a familiar everyday world: Géminis or Naciente XVI (both from 1963). Vigas combined informalism and expressionism with visual elements from figurative and abstract styles in the complex works that he carried out until the end of the sixties, most of which were made in Paris. At that time his painting was classified as Americanist, due to its telluric references that evoked pre-Hispanic man, homages and offerings he made to nature and the gods that only he was familiar with: Guardiana (1967). His free brushstrokes increased, as did the planes of color, which, although combined somewhat arbitrarily, created strong vibrations that in aesthetic and compositional terms brought life to the surface of the painting.

In La gran bruja and other similar paintings, Vigas uses the work as a vehicle to set out general questions related to the classic style of art many painters outwardly displayed. He continues to adopt the figurative codes of representation mentioned above, but alters them by fragmenting reality and reducing them to their minimum expression and maximum meaning, perhaps following Arnold Shöenberg’s advice: “Everything in art must automatically determine its own form”. Vigas captured the social, political and cultural whirlwind of the time and adapted to its demands, while he exceeded figurative conventions to establish connections between the real and the imaginary in order to transcend representation. By painting using a specific meta-language, Vigas evoked an enigmatic and mysterious atmosphere that establishes lines of communication between artwork and viewer. The link between form - figure-witch in terms of composition of the pictorial frame using relationships between color-line-form are both significant factors in this context.

The female figure dominates Vigas’ work consistently. He deforms her, makes her Baroque, de-structures and deconstructs her in order to reinvent her using bold lines of color on the canvas. His work developed with incredible speed and changed during each period, but Vigas always maintained his figurative core; he darkened or lightened his palette; substituted the flat surface for a textured one; dense matter and forms coiled up in space in an almost abstract expressionist way reminiscent of the North American expressionist school, outsider art and the Cobra group. Given the density of his paintings, his impulsive and free gestures, and the dark and violent colors and thick black lines of his works from the sixties, Vigas could be considered an unrepentant figurative and informalist painting. These characteristics continue to feature in his entire body of work. Even when the palette becomes lighter and he uses warmer, softer colors he continues to define the forms with the same usually black, thick lines: Duende rojo (1979), Mujer en rosa (1985), Tentaciones de mi adolescencia (1994), Diablesco (1999), Un canto a la vida (2003), Gran curandera IV (2009) and Mantuana III (2010).

It is worth recalling that the artist posits the figurative image as an autonomous construction of reality. His realism is somewhat paradoxical given no figure resembles the ones he creates because they are ultimately products of his imagination, rather than something that actually exists. Neither is it a modernist “comment” on the given subject matter; Vigas is interested in the visual aspects of a work that stridently presents its condition as painting. The ambivalence between the figurative and the abstract demonstrates the instability of figurative representation in an illusory dimension of reality. Both the format of the painting and the human being represented are given a vertical form. Whatever medium he uses, this is not all Vigas is suggesting in his analogies. Adopting a vertical axis and frontal position, he situates the character in the center of the composition so that it dominates the frame; this character, who contrasts to the apparently empty backdrop, displays an inner “body” marked by unfinished brushstrokes and blots of color of different sizes and thicknesses. The works conclude with a sort of chromatic narrative that responds to certain key characteristics in his painting, such as the familiar opposition of form and background, present as of the seventies but which takes on a more emphatic role in the large, stretched formats of the first decade of the twenty-first century: Gran curandera III (2008).

Throughout his artistic career, Oswaldo Vigas has continually created representations of an deformed image, internally off-kilter and made up of fragments that are recomposed using certain invisible “inscription” and formal “signs” that give clues about the figurative discourse. Vigas is an admirer of Wifredo Lam’s technique (La jungla, 1944), Pablo Picasso (Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907, and his Cubist collages), the deformed women of North American artist Willem de Kooning, and the pre-Hispanic Venus. He transforms form into an autonomous entity as he reproduces it entirely by using only the segments that interest him and his own formal limits and decisions so that, during the process, he can transmute the female body into an icon. Viga’s personal style is defined by deformation in figurative images and controlled abstraction as a teratological method of inquiry that defines how the form-figure-backdrop behaves on the pictorial plane and is based on the “sensation” of the image in the Cézannian sense. The formal aspects of his work that expresses the spiritual charge it contains within it are determined by the image which is transformed into an icon and doted with an ambiguous beauty. In an article written by journalist A. Feltra for the newspaper El Universal in 1979, Vigas said: “(…) there are things produced by the imagination and fantasy that span different worlds (…). When they are given artistic expression they act as vehicles for worries and longings that cannot be translated into words (…). We could call them “phantoms” and consider them part of the religious idea of angels and demons”.

It is important to refer to Vigas’ three-dimensional work as well. His sculpture is similar to his painting because he takes the essence from it in order to experiment in various ways. He is interested in the dialectic between different forms of expression, because each of them offers different options to create art that refers to the mysterious world of ancient civilizations and to the contemporary world, with all its problems and worries. The search for immanently expressive elements is key; Vigas thus strips the figure of all decorative possibilities to pare it down. He is interested in textures, the way the gaze enters and leaves the surface of three-dimensional works, as well as the volumes created when the light hits their hollows and solid spaces. In 1985 he presented his first bronze sculptures. Continues to this day his interest in sculpture, good examples would be Guardián (1994) Matadora (1997) y Garota (2007).

This summary of Oswaldo Vigas’ artistic career leads to the conclusion that his initial approaches to painting and drawing in the 1940s combined to produce a fantastical expressionism, a sort of set of oneiric scenarios that are given organic forms, and which dwell constantly on the figure-woman and landscapes. The end of this period was marked by a growing alteration of the female figure, which signaled that it would become the iconic archetype in Vigas’ work. This inquiry, which was vigorously present until the fifties, evolved into geometric stylized forms. At this point the artist placed emphasis on the material quality of the textures and lowered the temperature of the colors he used to increasingly use dark greys, ochers and greens. Towards the middle of the fifties he eliminated secondary elements to highlight the most essential elements of the figurative “presences” in his work. This process led to an oeuvre of black objects, somewhat sombre geometric paintings: Objeto vegetal, Objeto gris and Objeto americano negro, among others.

Vigas began the sixties by developing an interest in the informalist style and worked to emphasize the main features of his early work. He returned to the figurative style, which was enriched by his experience with informalism, and created the series Personagrestes, where the witch-woman theme predominated open compositions that featured lines and planes of color going in all directions. He diverted toward a brief abstract period that reduced the figure to a summarized geometric form, organized in almost monochromatic planes. The vertical, severe figures reappeared at this point and took up their almost obsessively dominant position in the center of the canvas until the eighties. During the nineties, Vigas continued his formal purging by making significant changes to the composition and deconstruction of the figurative image. As of 2000, the relationship between background and form became more pronounced, as well as the use of shades of white in order to add highlights to the composition. His works included all types of figurative images, recognizable of otherwise, that took on different functions in his aesthetic proposals and in the coherence of his subject matter. In conclusion, Vigas’ work centers on the expressive image in terms of ideas posited by universal art and on human beings’ sense of belonging. In short, the work is defined by iconic and psychological complexity that characterizes the figuration –or de-figuring– of contemporary art.

Oswaldo Vigas took on a commitment to art and a life spent in the studio, in different countries and among his family. The artist dies on April 22nd 2014 in Caracas.